The 75th anniversary of the Glorious Victory in the Great Patriotic War draws nearer, and we have prepared some information on activities of the Academy faculty and students during a part of WWII turmoil – 1941-1943.

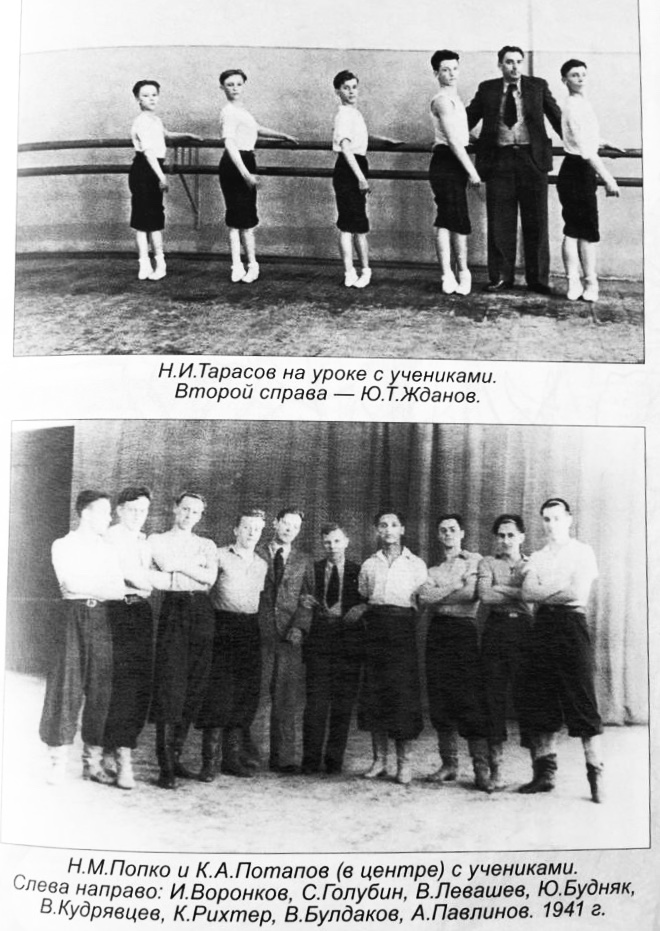

When the War began, most of the students of the Bolshoi Theater Dance School (the present Bolshoi Ballet Academy) were vacationing at Polenovo summer camp. A decision was made to evacuate the School. Led by Nikolai Tarasov, Merited Artist of the Russian Soviet Federative Republic, Artistic Director and Dean of the School, 94 students and 15 teachers and staff members were sent to Vasilsursk, a tiny town along the Volga. In 1941/42 winter, the School was accommodated in a timber building of water transport workers’ club, together with a general store. The building had no electric lighting, and at first, both students and teachers had to put their bedding right on the floor. That winter, the temperature in Vasilsursk dropped to 50 degrees Celsius below zero.

Step by step, students took care of their dwelling and training arrangements – they used rows of chairs as makeshift ballet bars. They made their costumes and stage property. They took charge of stocking up firewood and heating the rehearsal room. That winter, they wore body warmer jackets and sometimes even valenki (Russian felt boots) to attend classical dance classes.

N. M. Popko and K. A. Potapov with students. Left to right: I. Voronkov, S. Golubin, V. Levashev, Y. Budnyak, V. Kudryavtsev, K. Richter, V. Buldakov and A. Pavlinov. 1941

In due course, both students and teachers were duly accommodated in private apartments and in the local hotel; classes in general subjects began. Weekly schedule of the students included drill exercises, briefings on political circumstances and front-line situation, classes in local neighborhood history, along with herborization of medical herbs and some leisure activities – games and music.

Students took part in public and social activities – talked to soldiers and officers convalescing in the neighborhood, organized exhibitions on drawings and toys, staged literary soirees. In summer, students helped local farmers with their activities, gathered berries and worked at tree-felling sites. The School donated provision to the workers of Leningrad. The School even started its own farming business – students built a pigsty, brought some pigs and a cow, made hotbeds for farming.

In parallel, students trained to take part in a concert show, practicing classical variations, Belorussian, Moldavian and Dutch dances, as well as Chopin’s Mazourka. First concerts took place at the local hospital occupied by soldiers and officers recovering from front injuries. Students handwrote invitations to their concert shows.

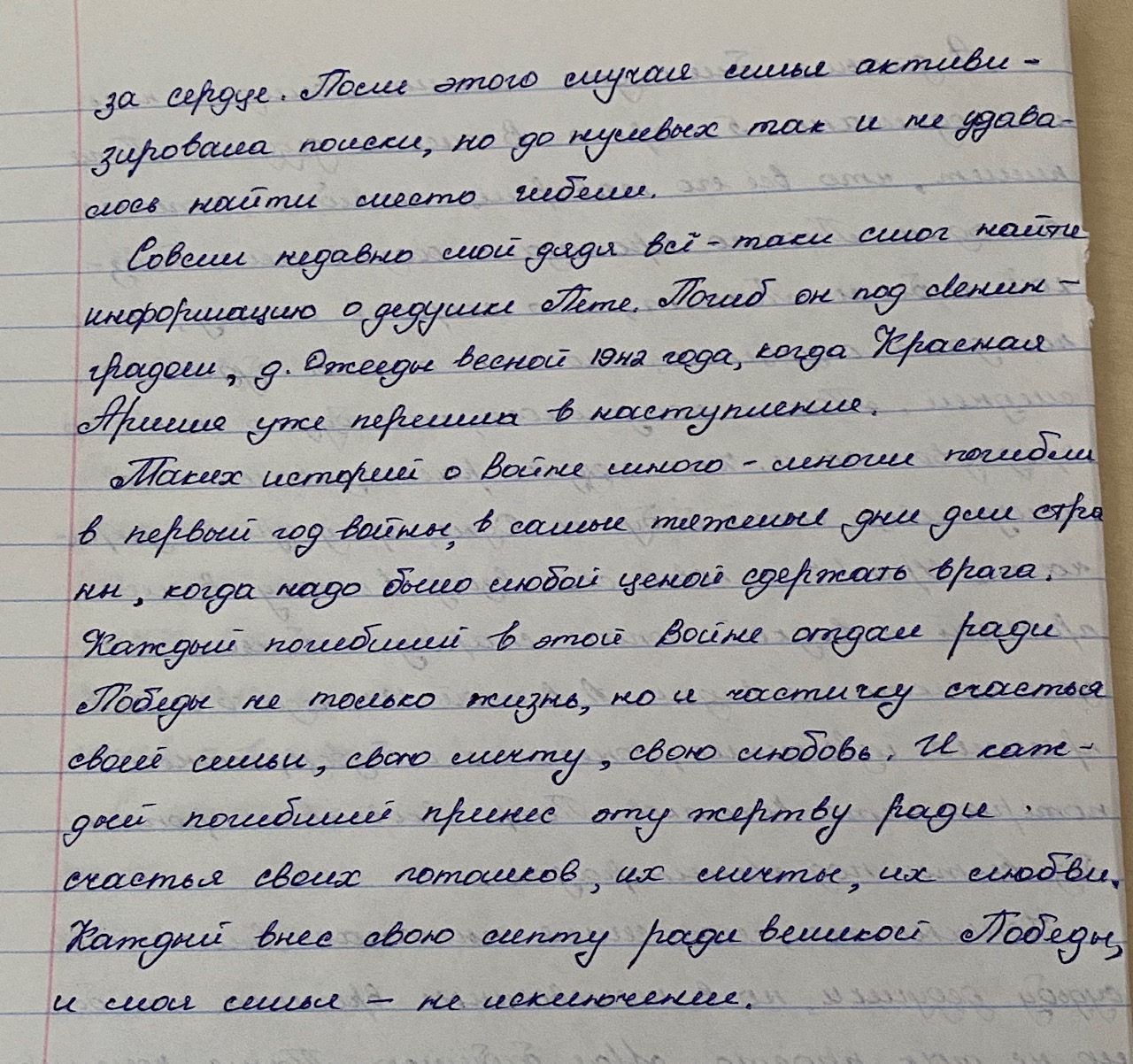

A new chapter in the story of evacuation site activities of the School began when the famous Soviet performer and choreographer Kasyan Goleizovsky came to Vasilsursk. Within days upon his arrival, Goleizovsky began rehearsals to stage a 1942 New Year ballet performance for children, with Konstantin Potapov’s music and his own libretto. Fedor Fedorovsky was the production designer. The show was staged in eight days. It was titled “Father Frost’s NY Party”. The show was a particular success during the evacuation time. The plot was based upon Russian fairy tales. The first scene includes a dance by Masha, the main character of the show, with her doll, Masha’s dream, a meeting with Father Frost who shows her a “fabulous Christmas tree with clockwork toys”. During the nest scene, the toys come to life, and a Merry-Andrew, Little Dolls, Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf, along with Tom-Thumb, a Cat, a Pussy Cat and other characters perform a divertissement. The finale was a coda performed by all young dancers participating in the show. The show was a real New Year miracle for those who saw it. K. Goleizovsky, the director, said “The show was a tremendous triumph. I feel a bit awkward praising myself, but I have to admit – the performance was a success in every sense”. For the Red Army Day , Goleizovsky staged a concert with numerous folk dances, including a Mazourka and a Russian Dance. Front-line soldiers and officers convalescing in Vasilsursk, praised the selection of dances. Folk dance numbers reminded them of their home places. Raisa Struchkova, famous Russian ballerina, People’s Artist of the USSR, was a senior when the School was evacuated. She recalled: “Soldiers and officers saw not just performers – they saw their children they had left behind, in us”. In 1941 and 1942, students of the School gave more than 100 performances.

Students and teachers created most of decoration and stage properties – they borrowed curtains form the local hospital to use as the stage veil, made toys for the Tree in the show, made tutus from cotton gauze and dyed them with makeshift dye-ware.

The School company performed on tiny makeshift stages, and most often the audience was seated right on the floor around little dancers. During the evacuation years, the School took the local military hospital under patronage. The School company performed for patients of local medical institutions, youth about to be sent to the front, collective farm workers, for children evacuated from other parts of the country, local residents of Vasilsursk and for soldiers digging trenches in the neighborhood. Doctors, officers, school students, etc. sent letters of gratitude praising the School for its support and performances. They are carefully stored in the Bolshoi Ballet Academy’ s archive. The School company toured the vicinity of Vasilsursk. For their performances, young dancers received jam, bread, etc.

The School spent two years in evacuation in Vasilsursk. Two years of constant hardships, hard labor and daily creative activities.

During the years of evacuation, many students of the Bolshoi Theatre Ballet School realized that ballet is not just stories of beauty and perfection. Ballet can give hope and heal souls that have grown rude because of horrors of wars. A brief time ago, they were scared half-frozen children hardly realizing the way to help their country and their people, but during the war years, they quickly became adults with clear understanding and conscious assumption of the mission of a ballet performer under wartime conditions. Raisa Struchkova gave an extremely precise account of their feelings: “As seniors of the School, we felt that what we did back then was unbearably insignificant – we had a permanent burning desire to do something meaningful to help the country and the front-line. Of course, everybody’s dream was to do something really heroic, to accomplish something meaningful, but harsh reality of everyday life required real labor – shifts and concerts at local hospitals, felling trees to stock fire-wood some of which we gave to the hospitals, helping local farms, mentoring younger students at the School…”.

Then the front-line began mowing westward, and in 1943, the School returned to Moscow.

*Excerpts from “The Moscow Ballet School in Vasilsursk (1941-1943)” by V. Teyder (Moscow, 2010) were used to prepare this material.